Paul Klee, a Swiss artist, describes his fantasy works as ‘taking a line for a walk’. It is a fundamental definition of drawing, which is the art of representing a figure or object by tracing its shape. Color, in contrast to this linear boundary of form, produces hues of varying lightness and saturation via pigments.

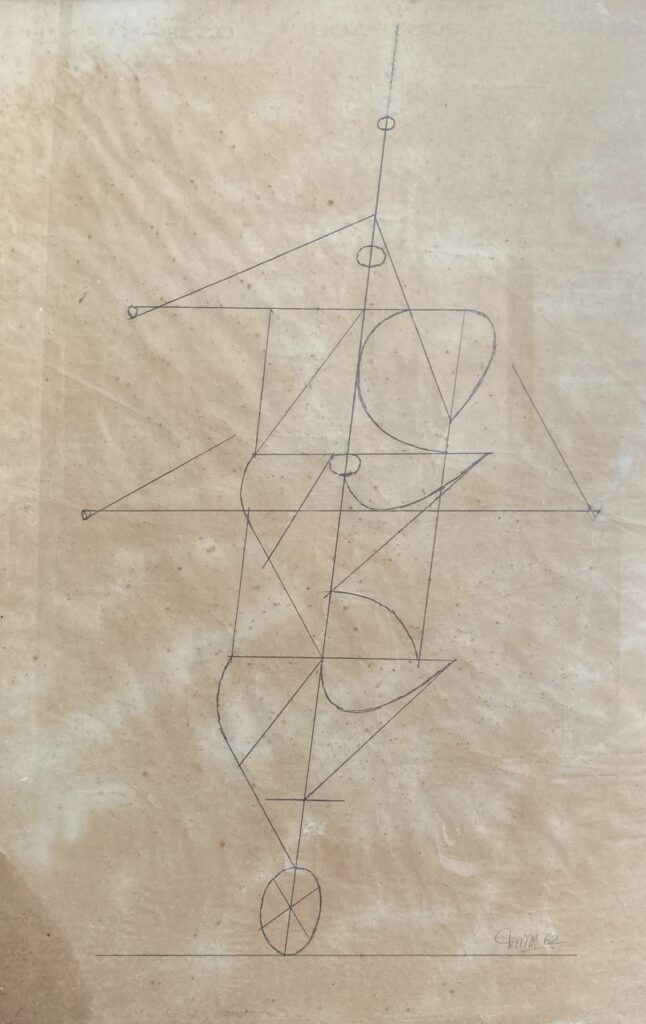

After a midday meal during the Japanese occupation, 17-year-old Arturo Rogerio Luz began drawing a portrait of his mother Rosario without provocation. Luz continued to draw until his death. Drawing is the foundation of his art, representing linear strength and elegance.

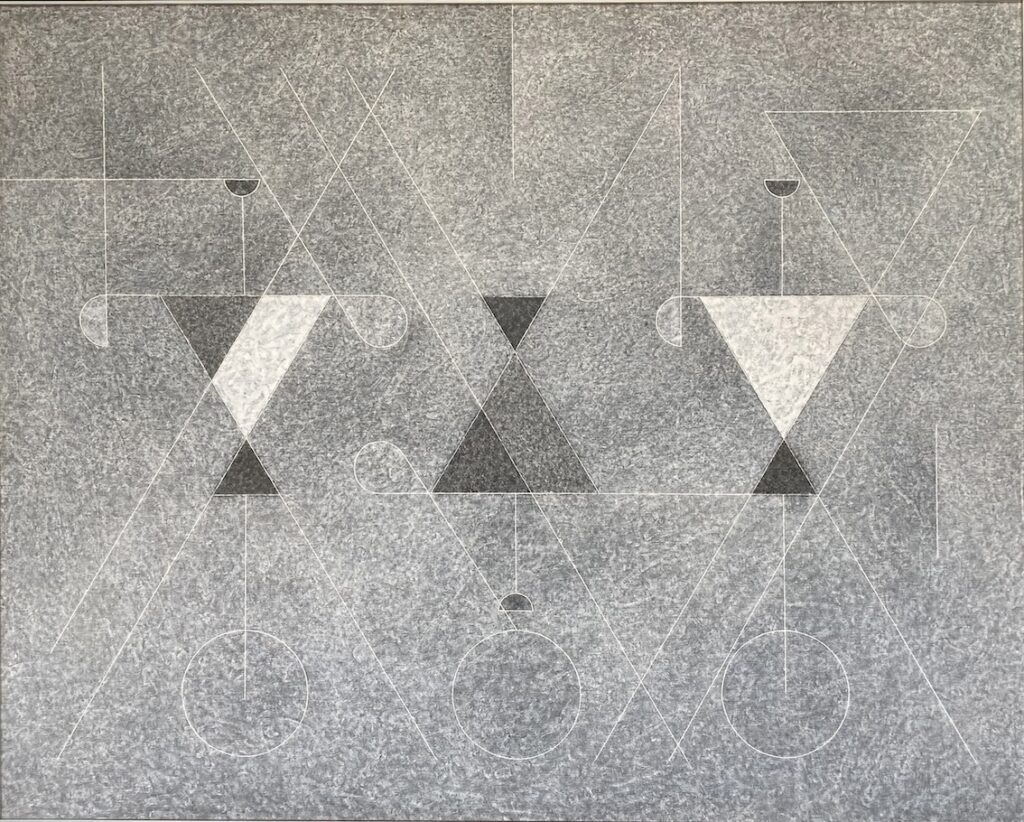

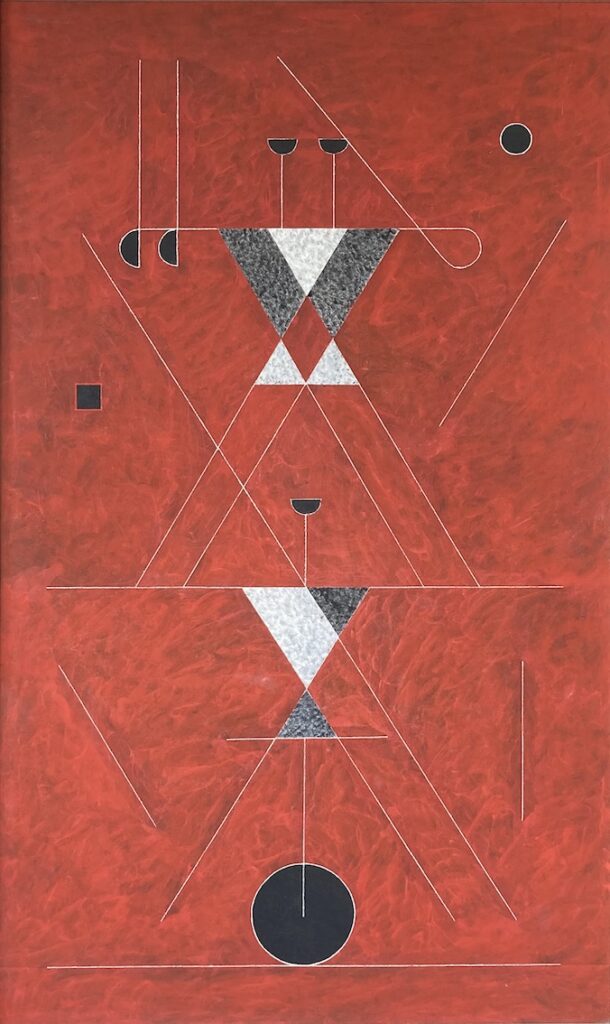

The multitude of lines moves intricately, capturing in their tight web the astonishing variety of his comparatively limited visual themes: cyclists, acrobats, musicians, performers, ancient pottery, and Asian architecture.

The origins of all these lean and attenuated figures can be traced back to a sight he witnessed during a New Year’s Eve celebration in the early 1950s. He noticed three men riding a rickety bicycle, maintaining perfect balance as they passed their street. Luz embellished the painting with a figure tooting a horn in the background. Luz considers this painting to be the most important of all. It’s appropriately titled “Bagong Taon. He realized that the framework of all his future works would be linear and geometric. The line was intended to function as both an ordering element and a system. Luz, a meticulous draftsman, knew the importance of elegant and disciplined design.

Arturo Luz enrolled in the College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, California. Three and a half years later, he enrolled in the Brooklyn Museum Art School after learning that an artist he admired, Mexican Rufino Tamayo, was on the faculty. Unfortunately, Tamayo had left the faculty a term before. Luz’s early works, including Labandera, Awit, and Madonna, reflected Tamayo’s stylistic influence.

LINEAR AUSTERITY

Luz, on the other hand, would be sensitive to Paul Klee’s linear austerity. Klee’s carnival forms and cityscapes will be distinguished by the electricity and energy they contain. He would give his strictly disciplined compositions a “snap” and a “spring.” Moonscape, Nightglow, White Kingdom, Ciudad del Pasado, and Venezia show off a dense field of spirited, acrobatic lines.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Luz was preoccupied with the mastery of his image selection, which included ancient pottery. Jars, bowls, and other vessel shapes arose from his now-iconic linear style. The pottery images demonstrated that the artist was more concerned with their essential, sensual forms than with the subject’s archaeological significance.

Luz began working at the collage in the late 1960s. Collage, derived from the French word coller, meaning to stick, is an artwork made up of cut or torn pieces of paper, fabric, plastic, leather, or almost any other material that can be glued to a surface. (Picasso’s use of torn French newspapers and wood caning in his paintings is regarded as the invention of collage.) Luz created an astonishing number of collages by cutting pieces of paper into geometric patterns of squares, rectangles, and circles and then overlaying them with acrylic pigments in various muted tones, often in earth and neutral colors. He titled these collages in honor of all the artists he admired, including Klee, Tamayo, Rothko, Matisse, Marini, Morandi, Modigliani, and Spanish abstract artists Tapies, Torner, Millares, Rueda, Sempere, Feito, Saura, and Zobel.

His decision to pursue sculpture coincided with Luz’s transition to total abstraction. Luz created his first sculptures in the 1950s. He carved Christ’s head and visage out of adobe. When Luz first started sculpting, he was inspired by the forms of pre-Hispanic deities known as anitos. He used Philippine hardwood blocks like molave, balayong, and supa. He eventually recast some of the anito figures in bronze.

LESS IS MORE

The “reclining” or horizontal pieces contrasted with the standing, upright anito sculptures, which were long, thick slabs of hardwood. Even in three dimensions, Luz adheres to the principle of “less is more,” which originated in architecture and was popularized by German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a pioneer of the Modern Movement. The axiom implies that good design results from simplicity and clarity, which is achieved by eliminating excessive and unnecessary components.

This writer once stated, “His virtuosity lies in his insatiable desire for design. The greater triumph is that when a design moves from painting to sculpture, it gains everything while losing nothing in its pursuit of plasticity and objective form.”

Luz was challenged and inspired by a wide range of mediums and materials, including burlap, a coarse heavy fabric used for bagging. The artist brought this unsightly material to life with stark black-and-white contrasts and subtle tones of sienna and rust. Again, elegant, intelligent design shines through in these burlap fragments, which are layered and composed to create vibrant, exciting designs. Dynamic equilibrium and fluid tension drive each arrangement. The gridded texture of the burlap added to the tactile appeal of these works.

Meanwhile, Luz experimented with handmade paper. Sumi-e brushstrokes enhanced some of his collages. Sumi-e, or “black ink painting,” was introduced to Japan by Zen Buddhist monks from China in the 16th century, and it has since become a staple of Japanese aesthetics. Luz also allowed black paint to drip from the tip of his brush, creating linear configurations and animating a space. He splashed black acrylic pigments in whirling strokes before reining in opposing blocks of solid color. Luz may have used gestural marks freely, but he did so with remarkable restraint and refinement.

Luz used brass and silver rods to create his cyclist and acrobat sculptures. He also experimented with jewelry, creating gold from quartz, lapis lazuli, and black onyx. Photography remained a constant in his work. As he traveled across the Asian and Indian continents, his eyes were constantly drawn to the breathtakingly beautiful scenery.

ASIAN TEMPLES, FORTS, AND PALACES Luz traveled on an annual basis, introducing a new and exciting subject: Asian temples, forts, and palaces. He captured the essence of these ancient and impressive buildings. Once again, the artist used his linear mastery to imbue these massive structures with lightness, airiness, and weightlessness. He titled the series “Cities of the Past.” These works began in the 1990s, transitioning from a rich and opulent color palette of reds and gold to the stark severity of black and white.

This prolific output of work over decades is even more remarkable when we consider Luz’s various managerial responsibilities. He was the executive director of the Design Center of the Philippines for 14 years, beginning in 1973. At the same time, he served as director of the Metropolitan Museum in Manila, where he presented 120 exhibitions over a 10-year period. He also served as director of the now-defunct Museum of Philippine Art (MOPA). Despite these numerous responsibilities, the eponymous Luz Gallery, founded in 1960, continued to exhibit the works of the country’s established and emerging artists. Despite closing after four decades of operation, the Luz Gallery established itself as the standard for newly opened commercial art galleries.

Luz received appropriate recognition and awards for all of his accomplishments. Among them are the Republic Cultural Heritage Award for Painting in 1966, the Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters from the Republic of France in 1978, the Patnubay ng Kalinangan Award from the City of Manila in 1980, the Gawad CCP Para sa Sining for Visual Arts in 1989, and the City of Manila’s Diwa ng Lahi in 1993.

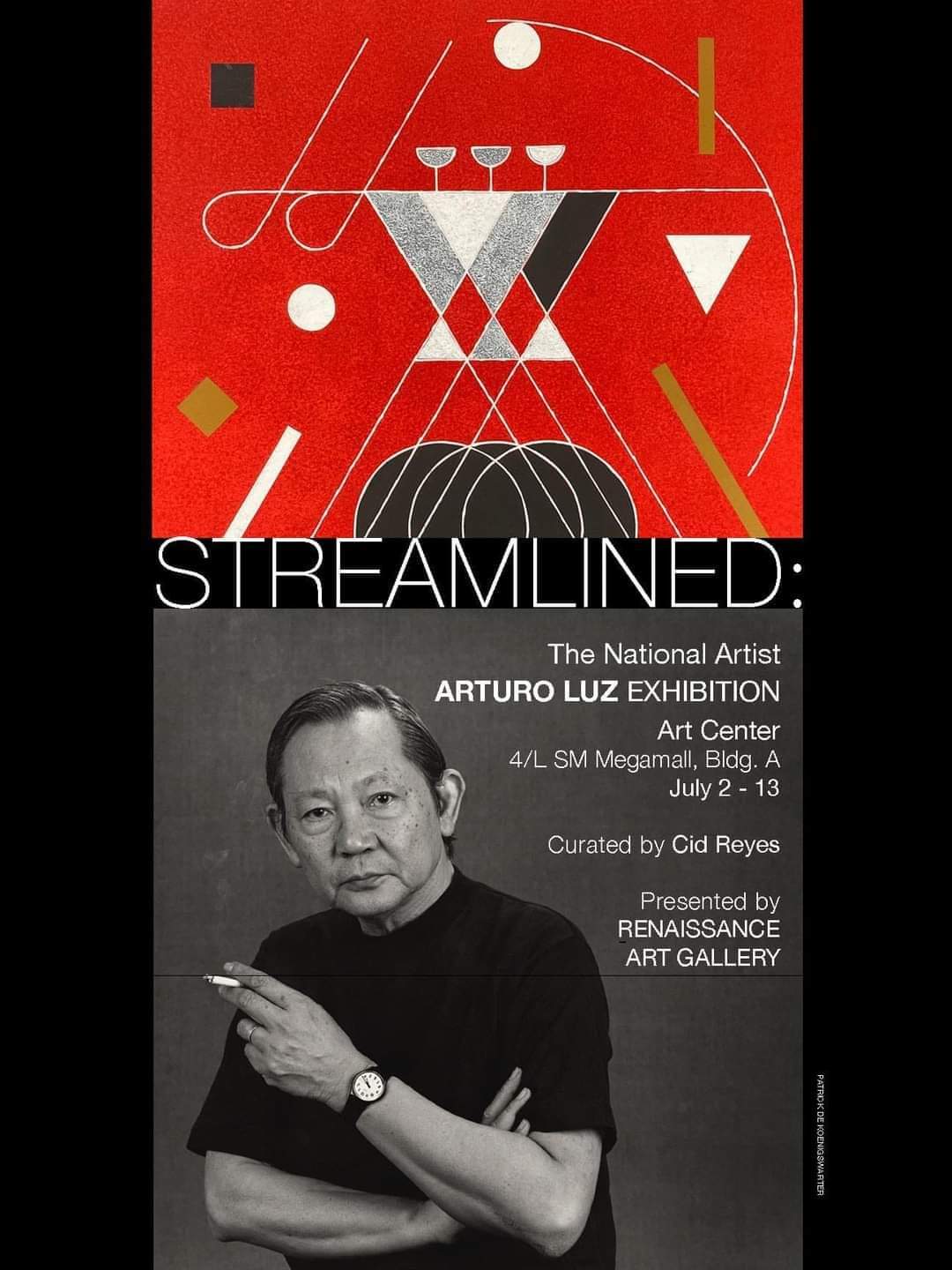

In 1997, Arturo Luz received the title of National Artist.

But he refused to rest on his laurels.

In 2009, Luz debuted a new series of large-scale sculptures in a show aptly named “Monumental.”

Corazon Alvina, former executive director of the National Museum, extols his lifetime work, writing:

“His art is expertly crafted, and his treatment of themes, both Philippine and universal, is eloquent and clear. Though logic prevails, visual pleasure is evident. No artist in the Philippine landscape has ever had such a profound influence on the pursuit of excellence and artistic integrity across such a broad spectrum while maintaining the intellectual independence required of all true artists.”

Despite widespread praise and admiration, National Artist Arturo Luz, the man who streamlined contemporary Philippine art, maintained a humble demeanor. He remarked, “In my own little world, I know precisely what I want to do. And for me, the greatest satisfaction comes from creating works of art. Nothing can compare to it.”

National Artist Arturo Luz died on May 26, 2021.